October 21, 1998 — Nkhata Bay, Malawi

It happens quite suddenly, and before I realize, it is too late. I am walking along one of the wooden makeshift ramparts of the Africa Bay Backpackers that separate people from the rocky and sandy terrain a few feet beneath when I suddenly feel a sharp pain in my right elbow. It feels like someone is pounding a spike into my joint with a sledgehammer. Then it vanishes. “Oh no.” Within the hour I am fading fast. I know something is wrong and I suspect malaria. We have been hearing stories abound about this rampant disease, and I am already paranoid. All it takes are some simple symptom in my body and I am convinced. I find Aren and ask him to take me to the hospital for some testing.

The Nkhata Bay Hospital is not like your average African big-city hospital. This place is compact, crowed and altogether a shanty in its own right. The whitish walls have been stained brown from years of weather and the corrugated roofing is completely rusted. There are people everywhere, mostly sitting, waiting and talking. A women under a tree to our left is selling BBQ corn. Other folks are selling things—mostly clothing donated to the village from some NGO—but nothing really of interest to a tourist.

We enter the main entrance and are greeted by a nice man, the hospital receptionist. “Hello my friends. How are you?”

“I don’t feel so well. I may have malaria.”

With a concerned look, the man responds, “Yes, this goes around now. To visit the doctor, you pay K30.00 (US $1.25.) If you like quick service, than you pay K60.00 (US $2.50.)”

I opt for the expedited service and promptly produce the required amount. I think I even tip a bit. The man asks us to follow him to a room behind the reception and down a musty hallway. “I am also the nurse; I must take some blood.” He opens a drawer, pulls out a sealed plastic wrapper, opens it, and asks for my left hand. I offer the receptionist/lab tech my right hand informing him that my left hand is my guitar playing hand and that it needs to stay puncture free. Laughter. Prick. Ouch. Dap, dap. Smear. My blood is now on a glass plate. The nurse then fumbles through some drawers and finds little bottles with multicolored liquids inside. He opens one of them, and with aid of a dropper, places a minute amount liquid into my blood and mixes. The man looks at me. “Yes, I am the lab technician as well.” We all laugh. I am quite pleased with the fast-track route of this hospital. The man then says, “One moment, the doctor will be with you in a moment.” And he leaves swiftly.

A moment later, the same man enters the room wearing a white coat. “Yeah, hello, I am also the doctor.” The man grabs the glass plate with my blood and sticks it under a microscope. He adjusts the mechanism’s variables and looks inside the world of Brian. Moments later he gestures me over. “Look in the microscope.” I peer in and see a world of circles and harmony. I notice that some of the circles have a dark entity around them. All to soon, I hear the words of the doctor. “It is Malaria, yes. Plasmodium falciparum.” The doctor is nonchalant, as if he is saying it is just the common cold or that it is a nice day outside. I pull away from the microscope in a panic. I look back with gazing eyes at the doctor who has a resolved and calm look on his face. He motions us to follow, and suddenly the receptionist/nurse/lab tech/doctor leads us to the pharmacy where he instantly transforms into a pharmacist and offers me a prescription for Fanzidar™, the current effective—almost too effective—malaria cure (that is banned in the US.) “Take this and if you don’t feel better in a few days, come back.” I pay another several kwacha for the medicine and bid farewell to my health care professional. I am in shock and scared.

Outside, Aren instantly proclaims, “Ja, you won’t be takin’ dat Fanzidar. Now is a good time to try out de ©Cotexin we have been carrying with us. It is the new Chinese cure dat all the overland truck drivers have been raving about. It is natural, has no side-effects, and much better dan dat lousy Fanzidar.” His Dutch accent is authoritative, yet soothing at the same time. He grabs the meds out of my hand and pockets them the way an angry mother would grab and dangerous item from a child.

Back at home (camp) Aren searches Leo (his and Marieke’s beloved blue 1984 four-door Land Rover Defender) high and low for the medicine kit. He finds the worn army medical kit and retrieves a package of ©Cotexin and gives it to me. “I don’t know Aren, maybe I should stick to the prescribed medicine. What if this doesn’t work?” But by this time, I am desperate and I don’t argue. My head is pounding, my joints all have nails in them, and it is 87° F outside and I am freezing cold. (My temperature later reveals itself to be 104° F.)

“104. Good God!” Exclaims Aren, “Dat is too high, dis, we are going to have to fix it. Marieke, grab Roland and Todd.” The whole posse appears, and upon Aren’s lead, the gang picks me up and throws me into the lake—the frozen, arctic lake. Sure it is Lake Malawi, the nicest tropical lake in the world with an average temp of 80° F, but to me it feels like the arctic ocean, a mere 29° F; only liquid due to the high salinity content. I scream, I yell, I eat tons of Tylenol Extra®, and my temperature finally stabilizes at around 102. When it rises again, and it always does with this ailment, I down more Tylenol and am subsequently thrown in the lake again. I religiously eat the ©Cotexin malaria cure and stick to a diet of Tylenol Extra® and water.

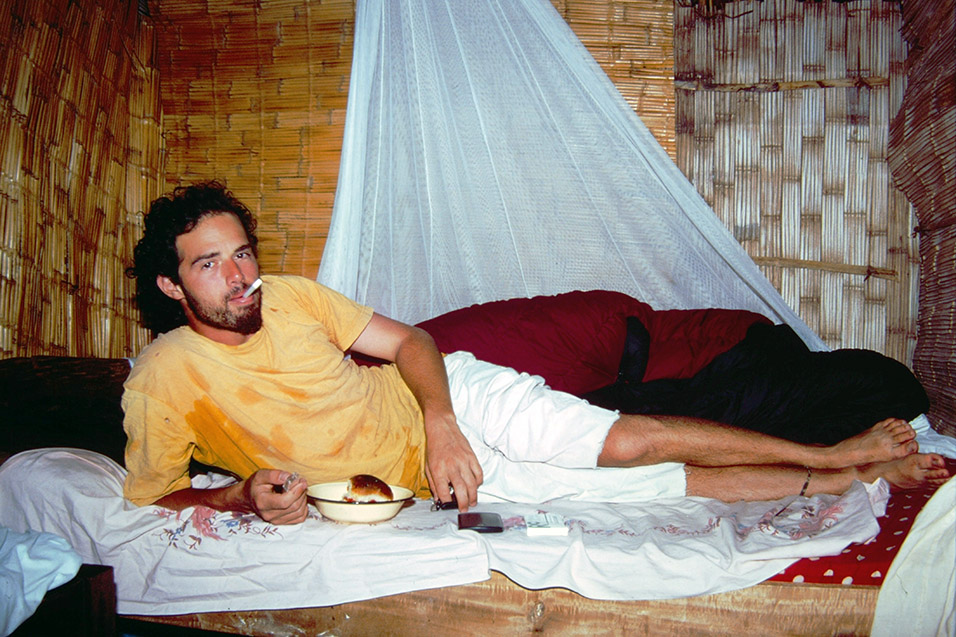

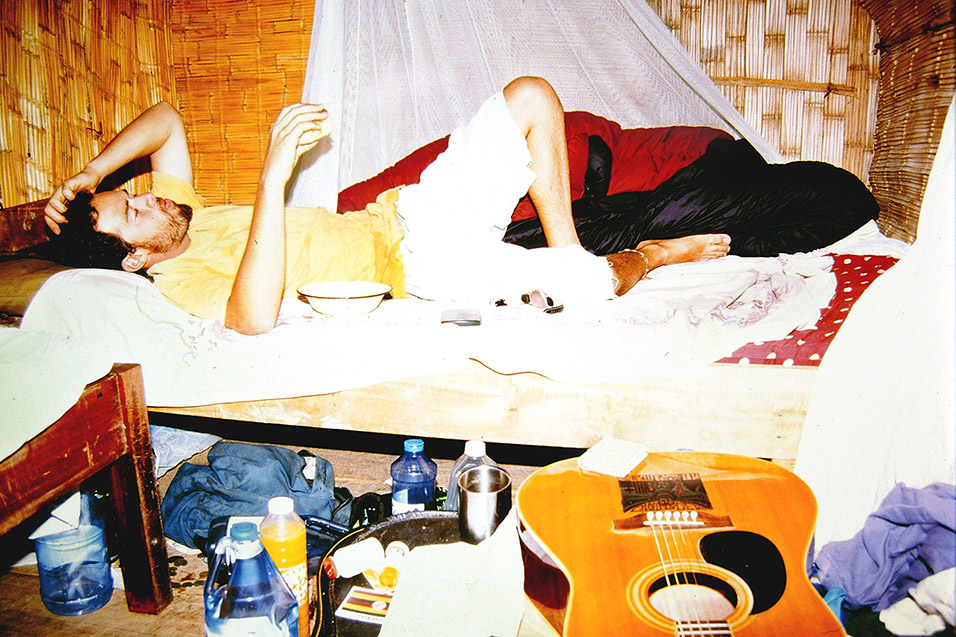

Nights with Malaria are the worst. I never can tell if it is the disease, the medication, or just the laying around all day, but I just can’t get seem to get any Z’s. Days are fine, there is light, people, the occasional being thrown in the lake. But night is an eternal bore, an endless blank. For three nights, I lay awake all night, doing nothing, just sweating and waiting for a glimpse of dawn and a bit of excitement. I don’t defecate for this entire time, but when I piss, the color is bright orange, almost red. I realize that this color is all the parasite ridden dead red blood cells being eliminated from my body.

On the forth day I finish all the medicine and I am starting to feel better, much, much better. Noting that I haven’t eating a bit the entire time, I realize that I am ready for some food. I call for one of the locals whom I have employed to care for me during my bout. “Old Jon, please get me some food and some water and some squash (the Malawi artificial juice concentrate in a plastic bottle.)” I give him K20.00, tipping generously. Moments later, I am face to face with food. “What a novelty,” I think to myself as I gorge through some rice and vegetables. I am in heaven, momentarily. But my bubble bursts, and the pain begins. “Oh no.” I run to the door. Suddenly, all my food is coming up the way it went down and is splattering all over the wooden ramparts and the ground beneath. My first meal in four days has been rejected. In a feeble and weak motion, I wobble back to my bed and lay down depressed. I begin to cry.

The next morning I am feeling a lot better and am able to down, and keep down, some breakfast. I thank the Lord for the mercy He has bestowed upon me. I did lose about 10 pounds, 10 solid meat pounds mind you, not water pounds. I look like Satan, and I do notice an odd stench emanating from my bed and my body, but that is OK. At least I am walking around. In that time that I had been down, I read the entire LP Africa on a Shoestring. I am in love with the continent. Malaria or no malaria, I want more traveling.

I emerge from my quarantine camp and walk, rather stagger downtown. The sun is hurting my eyes and burning my pale skin, but I don’t care. I am walking slow, quite slow, but interestingly, it is the same speed as the rest of the Malawians around me and I blend right in. I go to my local bean, rice and spinach lady and have my first good meal in days. The road to recovery is nice. Becoming healthy is feeling the most alive. The villains are draining from my body and life is being restored. It is at this point that I realize that healing is one of the most intense and positive of human emotions/experiences. I have survived my first bout with malaria. I sort of grin with the though. In a weird, convoluted way, I am proud with what I have experienced. I feel closer to the people and the land. I have loved the people, eaten the food, lived the life, and now, I have felt the pain, the pain of the millions who live here for eternity. Africa will now always be a part of my blood and my soul forever. (Too bad the Red Cross won’t be interested in my bodily liquid donations.)

I later learn that my case of malaria, Plasmodium falciparum, is the most dangerous, in that it can lead to cerebral malaria and death if left unchecked. But that it is also the most curable form. And once the host feels better, the parasites are eliminated permanently, unlike other strains which linger in the blood and liver forever. I also learn that, when it comes to malaria infection, the first time is the worst for a person. If I were to come down with malaria again, which is often inevitable in the tropics, I would get less sick. This thought is comforting. I smile and stroll on with my journeys.

One of the most difficult health question traveler’s face:

Risk of malaria vs risk of the liver damage due to long term exposure to anti-malarials.

There is no simple answer.

I tried both methods. And I did get malaria. Falciparum Plasmodium — the most dangerous and also the most curable. For me, it wasn’t that bad, but I took care of the problem immediately. If left neglected, the malaria may have killed me. Be prepared no matter what, ALWAYS have a cure with you. I think you should research what type of malaria is prevalent in the location and make your decision based on that. Again, in Africa, the common strain was falciparum (which is the most deadly, but the most curable: meaning once you are cured, it most likely won’t come back.) Other strains of malaria are less deadly, but they reoccur for the rest of your life. I really wouldn’t want to have the reoccurring malaria.

On another note, I met at least two travelers in E. Africa who were on Larium and still got malaria, but the drug masked the malaria tests for some time. What a really bummer.

Personally, I will never take Larium again as a preventative; too many weird side affects. I would take it as a cure, though. I would never take the Doxycycline. (The sunburns are too great - ouch.) I found the Paludrine/Chloriquine mixture worked the best for me. Then again, this was 1999, and a lot may have changes since then. Strains become resistant to the drugs. I think the best bet would be go to India, go to a Pharmacy, and ask a local professional what they suggest. They will be a lot more versed on the malaria scene than any foreign expert will. Definitely get a couple of opinions, though. (Some meds require a week or 2 or 4 before they become fully effective.)

I found malaria to be most prevalent during/after the rainy season and in the countryside.

I also noticed that malaria seems to come in epidemics. The locals seem to know best, again. I was warned that there was malaria in the region, and sure enough, I came down with the disease two months later. Listen to the locals. Also, if it hasn’t rained in a while (dry season) your chances of getting the disease are less. Remember, this is a living organism, it has it time/place where it strives. And it also has environmental limitations. This is not a mysterious entity that will get you no matter what.

As a final note, I traveled with a couple whom only used sprays for two years in Africa, and never got malaria. And they did it all: rain, dry, north, south, desert, jungle. But, I ask, what the heck is in those sprays??? No chemical regulations in the developing world. Good luck. And keep a positive attitude. And if you feel a sudden fever, and the sensation that someone is pounding a spike into your elbow, don’t panic, simply go to the nearest hospital. In my case, the nearest hospital was a dirty building in Nkhata Bay, Malawi. But the doctors there had me on the mend in no time.

As a follow-up, I took Fansidar as prescribed to me by Dr RH Roxin of the

Roman Catholic Hospital

Box 157 Windhoek, Namibia

061 237237

Countries visited - Africa 1998 - 1999

I am not sure how it all got started. It wasn’t a magical spark of lightning that began the cataclysm, nor was it the supreme words of a higher being sending us on our way. Somehow, though, the powers of the universe contrived enabling our journey through the Heart of Africa.

It began quite innocently as an alleged trip to Bulgaria and Romania. This idea was eventually vetoed and placed “on hold” for future girlfriends. Zap—a long awaited spark was kindled—The Middle East: Yemen, in particular. And the visas were applied for, the air tickets purchased; and on a fine March 4th day we were on our way aboard a gleaming Air France 747 en route to Cairo, Egypt, via a five day layover in France.

We never did make it to Yemen, nor the Middle East for that matter; we headed South, instead, into the Heart of Africa, and what follows is the story of events as they unfold.